When you first meet Ugandan artist Yiga Joshua, what strikes you is not just his quiet confidence but the depth of meaning behind his work. He doesn’t just paint. He heals, questions, and preserves. His art, most recently centered around banana fiber dolls, is not a gimmick—it’s a deeply personal and cultural journey rooted in memory, loss, and identity.

A Childhood Rooted in Creation

Joshua’s journey as an artist began in the most organic way—helping his mother, a primary school teacher, make learning aids. “I used to assist her in drawing goats, cows, apples… and building 3D geometric models out of manila paper,” he recalls. By the age of five, he was already working with his hands, crocheting and creating. When his mother passed away, he went to live with his grandmother, but his relationship with art only deepened. “Art gave me freedom,” he says. Even in primary school, he gravitated towards sculpture and painting—forms of expression that felt instinctive and liberating.

Art, it turns out, runs in the family. “My father was an interior painter, some of my uncles are graphic designers. My grandfather was a tailor—he was into fashion. It’s in the blood,” Joshua says.

Defying Doubt, Embracing Purpose

But like many artists in Uganda and beyond, Joshua’s career choice was questioned. “My father was a painter, and he had struggled. So when he saw me going down the same road, he was worried.” Still, Joshua was adamant. “I told him, ‘This is what I want to do.’” Eventually, his father came around. “He even attended one of my biggest shows in February 2023—and he loved it and was proud of me.”

The path was never easy. “People often compared us to doctors or lawyers—as if art was for failures,” Joshua recalls. Financial pressure also loomed large. Many peers gave up early on, convinced art couldn’t offer a sustainable life. “Ironically, that pushed us harder,” he says.

Art as Voice and Refuge

What’s most striking about Joshua is his refusal to let art become transactional. “If I was in it for the money, I’d be painting portraits full-time,” he says with a smile. Instead, his art became a voice—a way to process the trauma of losing siblings, navigating grief, and growing up in difficult circumstances.

“I don’t paint to decorate,” he says. “I paint meaning.” His works speak to trauma, loss, orphans, grief, and childhood—particularly the vulnerabilities he witnesses through his work with Fields of Dreams Uganda, a nonprofit supporting children.

“For me, art is healing. If money comes after I’ve healed, that’s great. But healing comes first.”

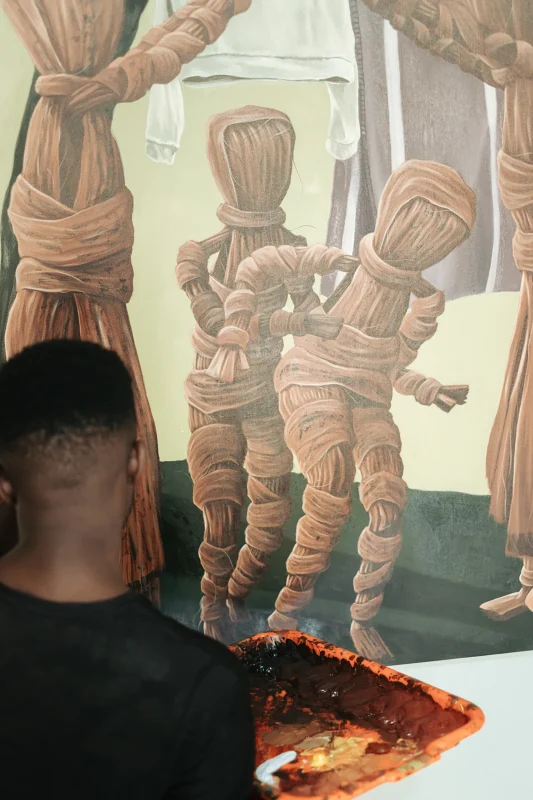

The Story of the Dolls

In 2021, during a period of introspection, the idea of the banana fiber doll emerged. During university, Joshua had pitched the idea of representing humanity through faceless figures, but it didn’t align with academic expectations. It wasn’t until COVID-19 slowed everything down that he revisited the concept—and the dolls reappeared, drawn from childhood memory.

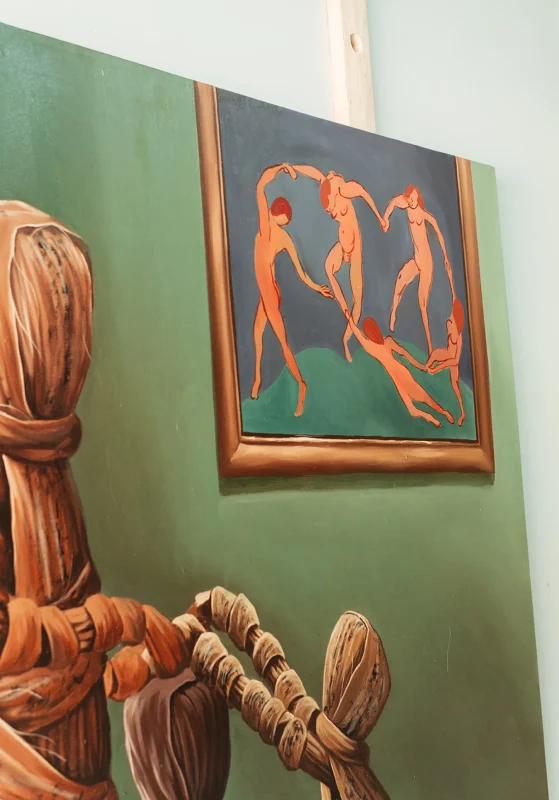

“These were dolls we used in the village—made from banana fiber. Simple, faceless, but full of life,” he explains. Inspired by American contemporary artist; Kaws. and guided by his own nostalgia, Joshua began painting and sculpting dolls as vessels of meaning. “They don’t judge. They don’t carry fixed identities. They’re human-like, but universal.”

The very first doll painting, when the idea struck; titled In the Beginning, was left unfinished, he collected it and kept it for himself because of its significance to him.

His fascination deepened as he researched the symbolism behind them. “Bananas share 80% of human DNA. The dolls had a life cycle—you’d untie them and return them to the garden, just like we return to the ground when we die.” For Joshua, the dolls represent an entire philosophy of life and memory. “We were all once dolls—in the imagination of our parents.”

He sees his work as preserving culture. “People ask how I preserve banana fiber. But I’m preserving the story. Paintings can last 500 years. The fiber won’t. So I paint them into permanence.”

Beyond the Canvas

Joshua’s commitment to the dolls extends beyond personal artwork. His installations often involve children, passing on traditional knowledge and craft. “They help build the pieces. They learn. And when people see them, they ask how they can make their own.” He’s even had international schools request to use his art to teach about African cultural practices.

He dreams of offering materials at future exhibitions so audiences can create their own dolls—turning each exhibition into an act of communal memory and renewal.

Staying True to Self

If there’s one thing Joshua wants to be remembered for, it’s authenticity. “I don’t paint to please anyone,” he says. “If a story doesn’t align with me, I can’t execute it. I want to be remembered as someone who stayed true to himself. Someone who brought joy and light, even through struggle.”

A Vision for Uganda’s Creative Future

Joshua sees a future where Uganda embraces its artists more fully. “We need museums dedicated to visual art—not just archives of national history, but spaces where the work of living and past artists is celebrated.” He imagines a country with more grants, residencies, and international collaborations. “Right now, opportunities are locked away in small circles. I dream of a creative ecosystem so rich, only the lazy would miss out.”

In the quiet strength of his voice and the layered complexity of his work, Yiga Joshua offers a powerful reminder: art isn’t just decoration—it’s memory, healing, protest, and preservation. In a world that too often forgets, his banana fiber dolls stand as soft-spoken heroes—carrying stories, culture, and hope forward for generations to come.